Wild turkey populations were once a sliver of what they are today.

Hunters are often considered the original conservationists. They’re the people who lead the way on conservation efforts that combat habitat destruction and aid in wildlife restoration of species that have had their populations devastated. Whether it’s through habitat loss, poaching, or a loss of food sources vital to sustaining the species, hunters can and will do things to help.

It may be hard to believe, but many beloved game animals were once in danger of extinction. American bison were nearly wiped off the plains, and ducks were killed by the flock with each shot from gigantic punt guns. Even the whitetail deer faced troublesome times due to overhunting. It was only through bans on market hunting and the tireless work of hunters, industry stakeholders, and state and federal wildlife agencies that the species made a comeback.

While there are several great examples of wildlife conservation at work, there is probably no greater conservation success story than that of the wild turkey. It took a lot of time and hard work for these beloved birds to be restored to the populations we know and love today.

How the Wild Turkey Was Nearly Wiped Out

Before it became a symbol of the success of wildlife management, the wild turkey was seen as a prime food source. According to the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF), some 10 million birds inhabited North America prior to European explorers.

Meleagris gallopavo (the wild turkey’s scientific name) were hunted by humans during this time, too. Native Americans regularly harvested gobblers for food and made use of feathers and other parts for clothing. However, as Europeans began colonizing America, the population of eastern wild turkeys and several of its subspecies slowly began dropping. It would continue that way until the early 1920s when the NWTF estimates only around 200,000 wild birds were still roaming the wild.

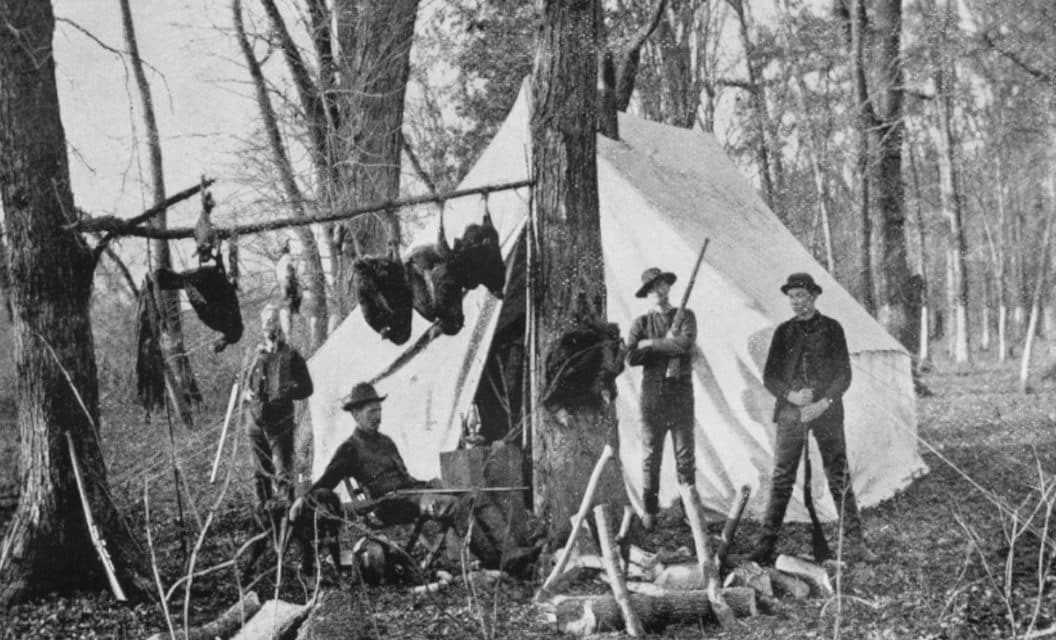

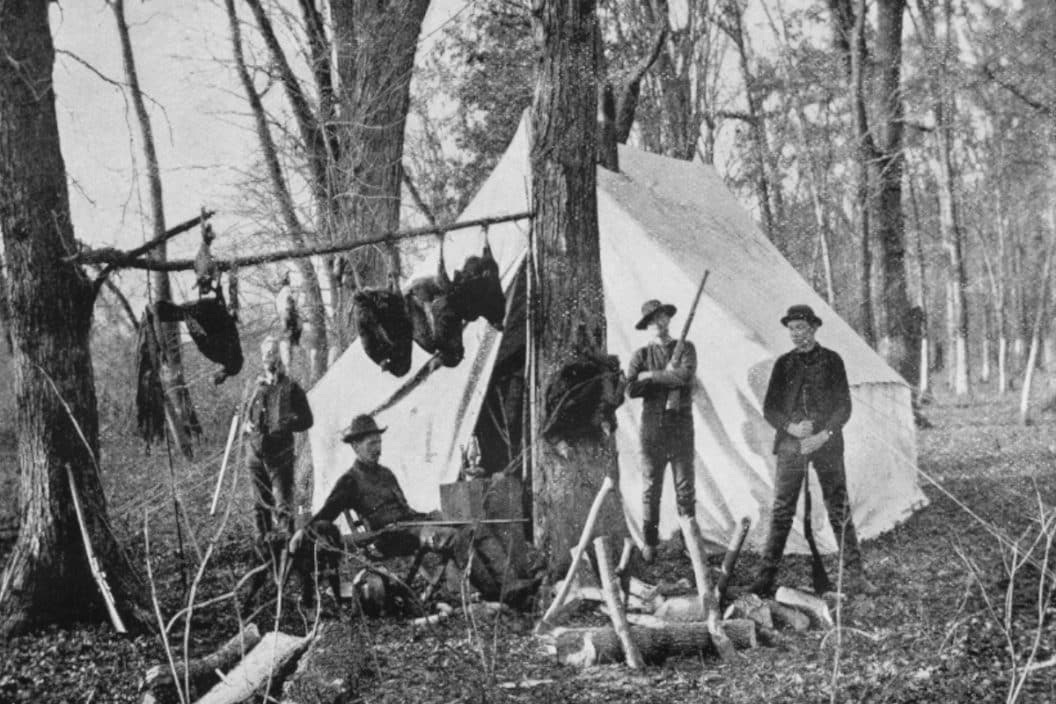

So, what the heck happened? For one, the influx of European settlers was simply too much at once. Most of those early settlements had no structured hunting seasons or bag limits. There was a massive demand for food as many of these settlements grew, and with no regulations to protect them, turkeys were harvested with a reckless abandon.

“Accounts list single-day harvests that often numbered in the hundreds of birds,” an NWTF document states.

Turkey hunting was commercial too, which didn’t help matters either. As market hunters were also harvesting birds to sell, the turkeys were getting wiped out faster than they could reproduce. It doesn’t take long to devastate a species’ population when it is being relentlessly hunted in that fashion.

It also didn’t help that suitable habitat for turkeys was getting eliminated quickly. The settlers cleared forests, both for commercial logging efforts and to start settlements and farms.

There actually were a few attempts to slow the decline of the turkey. The NWTF says Plymouth Colony was one of the first to pass a conservation law limiting logging in 1626, and New York started a deer season in 1706. Unfortunately for both the deer and the turkeys, this was a little late. The populations had been devastated. Most New England states like Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Vermont were devoid of turkeys by the mid-1800s, as were large portions of Canada.

The Stage is Set for a Conservation Success Story

Getty Images: Jens Lambert Photography

By the time the 1920s and 30s rolled around, North American turkey numbers were at their lowest points in history. In more than a dozen states, there were no more turkeys around at all. For the most part, their populations were mostly in isolated locations where there were still trees for them to roost and cover to hide.

Not much really happened with the conservation status of these birds during World War I and most of the Great Depression. For obvious reasons, the concerns of the nation were on other things. However, as horrible as it was, the Great Depression ended up being a blessing in disguise for stressed wild turkey populations.

“During the Great Depression there was a wholesale abandonment of family farms, as some 14 million rural Americans left their homes in search of work,” the NWTF says. “As these farms slowly reverted to native grasses, shrubs, and trees, wild turkey habitat began to emerge.”

At the same time, there were several key conservation milestones that helped to further protect the game birds. Enter Iowa Republican Representative John F. Lacey. In 1900, there was still a lot of commercial hunting being done in the U.S., and Lacey realized the era of market hunting and punt guns needed to end if Americans wanted to have any wildlife left at all.

So, he introduced the Lacey Act of 1900 to Congress, and it was later signed into law by President William McKinley. This was an immediate win for wildlife since it outlawed the practice of market hunting by prohibiting the transportation or selling of illegally harvested game animals across state lines.

Then, in 1937, the Pittman-Robertson Act was established. This Act created an excise tax of 11 percent on things like guns, ammo, and hunting licenses purchased by sportsmen and women everywhere. The funds generated by the tax were directed towards state agencies and were used for, you guessed it, conservation projects, including the restoration of wild turkeys to their native range.

Finding a Way to Re-Introduce Turkeys

Unfortunately, one of the first restoration efforts for wild turkeys ended in a complete and total failure. Biologists originally thought turkey populations could be restored by re-introducing pen-raised turkeys to the wild. We can’t blame them for having this idea. After all, fish hatcheries have been incredibly successful the world over when it comes to re-introducing endangered species to their native fisheries. However, it just doesn’t work with turkeys. Hundreds of thousands of birds were released into the wild, and almost all met an early demise.

The problem was in the turkey’s very nature. Turkeys raised by humans from poults instead imprinted on humans and became conditioned to their presence, which made the pen-raised birds easy targets for both human hunters and predators. As the NWTF notes, without a mother hen to teach the young poults how to survive in the wild, their chances were extremely low, and these releases resulted in almost universal failure.

That left only one option: trapping and transporting wild birds into new locations. Wildlife biologists tried many ways of doing this in their restoration efforts. They even tried some traditional Native American trapping techniques. However, what proved the most efficient was the use of cannon nets.

These were originally designed for ducks and geese, but the biologists found they worked quite well for turkeys, too. While this method of reintroduction was no doubt stressful on the captured birds, it worked. The re-introduced Meleagris gallopavo slowly began to make their comeback from states where they had been wiped out previously.

Wild Turkey Numbers Today

It took a while for many populations to re-establish themselves after the relocation efforts. However, slowly but surely, hunters started to hear that tell-tale gobble echoing through their neck of the woods again.

As turkey numbers rebounded, regulated hunting seasons were re-established. It’s safe to say these birds have completed their comeback. In 1973, when the population was at around 1.3 million birds, the National Wild Turkey Federation was founded with a mission of not allowing the decline of the turkey to ever happen again.

We think it’s safe to say their efforts have been successful as the current population is estimated to sit somewhere around 7 million birds. Here in Michigan, I’ve noticed the increase in birds from the 1990s until now. Where I used to see hardly any birds, I cannot go through a single game camera card pull without a bunch of gobblers taking up a significant amount of the photos.

Turkeys haven’t quite rebounded to that estimated 10 million mark that was estimated pre-European explorers, but we’re guessing they’ll get there eventually.

The success of the wild turkey’s return can be directly tied to the key conservation movements of the 20th century, and in essence, proves that the conservation efforts of hunting work.

Can you imagine a spring without turkeys? We certainly cannot, and that’s why we’re thankful to the pioneers of conservation who helped make it happen. We’re only hoping we can follow their example and be equally successful in our efforts to protect and preserve our precious natural resources.

For more outdoor content from Travis Smola, be sure to follow him on Twitter and Instagram For original videos, check out his Geocaching and Outdoors with Travis YouTube channels.

NEXT: SPRING TURKEY HUNTING TIPS: 15 QUICK ONES TO HELP YOU HARVEST A BIG GOBBLER

The post Wild Turkey Conservation History: How Gobblers Made Their Historic Comeback appeared first on Wide Open Spaces.