I’m going to get right to the point. Your photo archive is in danger, and you may very well be at risk of losing everything. Be afraid. Be … very … afraid.

Yes, I’ll admit it. I am dramatic, even for an alarmist and professional paranoid conspiracy theorist. But as a photographer, I also know firsthand that few things are as precious as our photo archive. We’ve poured our money, our time, our feelings and even our souls into what we’ve created over years of work. Ergo, logic dictates that at the very least, we should take a bit more care in protecting something that is so precious to so many of us. So please, allow me just a little dramatic latitude here.

Now, the goal of this article is not to scare. I mean, I want to initially, but it’s not the overarching goal. How does that saying go — we protect what we love? However, we will only protect what we love once we are aware of its potential loss. By instilling in you the potential loss of your precious assets, I feel I can steal your attention, so we can then focus on the real goal of this article. Actually, we can then focus on the real goal of this four-part article series on keeping your photos safe, which this article is kicking off.

The real goal is to help provide you with the knowledge and tools you need to safeguard your work, to battle “bit-rot,” to fight off the drive failures, to conquer file corruption, to combat the natural disasters, and to never accidentally delete your work.

Keeping Your Photos Safe: What Could Go Wrong?

In short, there are two kinds of storage devices sold on the market today. I don’t care how you look at it, or what industry data you reference, there are either hard drives that have failed or hard drives that are going to fail. If it hasn’t happened to you yet, it’s coming. You can choose between SSDs (solid state drives) and HDDs (hard disk drives), but both can fail anytime, and both can fail catastrophically. These drive types work very differently from the other, so how they fail is different. Either way, step one in the fight to safeguard our photo archives is to know what threatens our data.

SSDs appear to be the wave of the future. Their prices seem to be coming down by the week, there are more options than ever before, they have no moving parts, they are not nearly as susceptible to damage from shock as HDDs, they are lighter and more compact, and they are faster than your traditional HDD (often times much faster). If you want to speed up your computer and are still using HDDs, try moving to an SSD; the difference is quite noticeable. But SSDs are also far from perfect.

Most all SSDs sold today store their data in NAND flash memory cells. NAND is not an acronym and refers to a “NOT AND” logic gate, which is a type of flash memory that reads and writes data in blocks. One of the key limitations to flash memory is that the number of times these cellblocks can be programed and erased is finite.

There are well-manufactured SSDs and SSDs that are carelessly manufactured, so not all SSDs are created equal. Some can last 15 to 20 years under normal use, and some will last a few years (or less). A larger looming problem is that when flash memory fails, it often fails without warning, and the failure is more commonly catastrophic, meaning you lose most if not all of your data, and recovery, when possible, is costly.

Furthermore, even though the key feature of SSDs is that they store data in the absence of power, they don’t favor its absence for extended periods of time and are subject to a thing called “electron leakage” if they are. I’m not suggesting you use your flash drives and cards every day to avoid this, but leaving a drive unpowered for a few years and then starting it up expecting everything to be perfect is tempting fate. SSDs can also lose data in abnormal temperatures or when subjected to static charges.

HDDs are also an imperfect tool. HDDs are equipped with a “hard plate,” which is a rapidly spinning magnetic metal or glass plate. When I say “rapidly,” most HDDs spin at 5400 RPM or 7200 RPM (revolutions per minute). The 7200 RPM drives have faster read and write speeds, so if you want better performance, go with 7200 RPM.

Naturally, all these rapidly moving things can fail, like anything mechanical. Electronic motors can fail. If your hard drive is bumped or jostled while spinning, it can cause a major “head crash” (the head is the component in the drive that does the reading and writing, similar to a turntable stylus in design), and you can lose data if there’s a sudden power failure while the disk is writing.

Hardware aside, it’s possible to also have an HDD fail as a result of introducing corrupted data (usually self-inflicted) to the drive — this is a logical failure as opposed to a physical failure. Still, HDDs are far more affordable than SSDs, finding high-capacity HDDs is far easier, HDDs are less susceptible to abnormal temperatures, and HDDs read/write lifespans are, in theory, infinite.

Comfort Versus Speed

So the question becomes, should you choose SSDs or HDDs? Personally, I use both. There are stages of my workflow where speed and high performance matter more, and stages where security matters more. In short, I suggest using HDDs for all your long-term storage, and use SSDs for everything else.

We outdoor photographers tend to store data on one system while in the field and then store it on another back at our home or studio. Assuming you are one of these photographers, I suggest your field equipment be optimized for speed with solid state drives. Portable SSDs, as of the writing of this article, are now available to consumers at relatively reasonable prices. Hot on the market are Samsung, Western Digital and SanDisk SSDs that start in the range of $100 for 250GB drives to $350 for 1TB drives. Portable SSDs are half the size of your typical 2.5-inch HDD portable drive, and they are much faster. Using those along with a laptop also equipped with an internal SSD will make the performance of your field equipment soar.

HDDs may be a bit slower than an SSD, but I suggest using them for all of your archiving, including backups. It’s true that both SSDs and HDDs can fail, and there are different opinions and different data sets that say one is just as safe as the other, one is just as durable as the other, or one lasts just as long as the other. Just know this: Nothing is 100-percent reliable. So, the key to keeping your data safe doesn’t rest on your choice storage device

Data Corruption

In addition to hard drives failing, data can also degrade or die slowly over time. Data degradation, colloquially known as bit decay, or bit-rot, is a rare but corrosive problem that can infect our hardware without us knowing it. The problem with data degradation is that some or most of your photos may appear fine, but under the hood things are very wrong. And the potentially bigger problem with data degradation is that if you create a backup of your infected data, you have also backed up the cause of the data degradation. This means data you recover in the event of a hard drive failure is corrupt data. Thus, one of the tricks in keeping our data safe is making sure that the integrity of your backup is flawless.

Then there’s my biggest challenge, the human brain. I must admit I’ve made terrible mistakes. On more than one occasion, I’ve accidentally thrown away large chunks of valuable images without knowing it. Fortunately for my ego, what I’m referring to is not unheard of. It happens. Here’s a scenario. What if you tell Lightroom to “Delete From Disk,” thinking only a couple of images are selected, but in fact you had a couple thousand selected, just because you held down the shift key while selecting without realizing it? The thought is crazy, I know, but such a thing has happened to me, and I didn’t catch my mistake for several days. I had no idea that I had done this and was in a panic when I discovered I did, to say the least.

But that’s not all. Data corruption can also result from faulty cables or card readers. Many times I’ve done a visual inspection of a recent import to find corrupt files, subsequently troubleshooting my way through my workflow, isolating my problem to one of these simple components. As a result, there are a few rules that I go by when transferring data. For starters, once I click “Import” in Lightroom, or once I initiate some kind of data transfer from card or camera to computer, I don’t move or touch any of the hardware involved until the data transfer is finished. Jostled cables or card readers can corrupt data, or even a whole import. I also suggest not to edit or delete images in-camera, to try not to fill up your memory card in the camera completely, and never — and I mean never — reformat your memory card until a backup is verified.

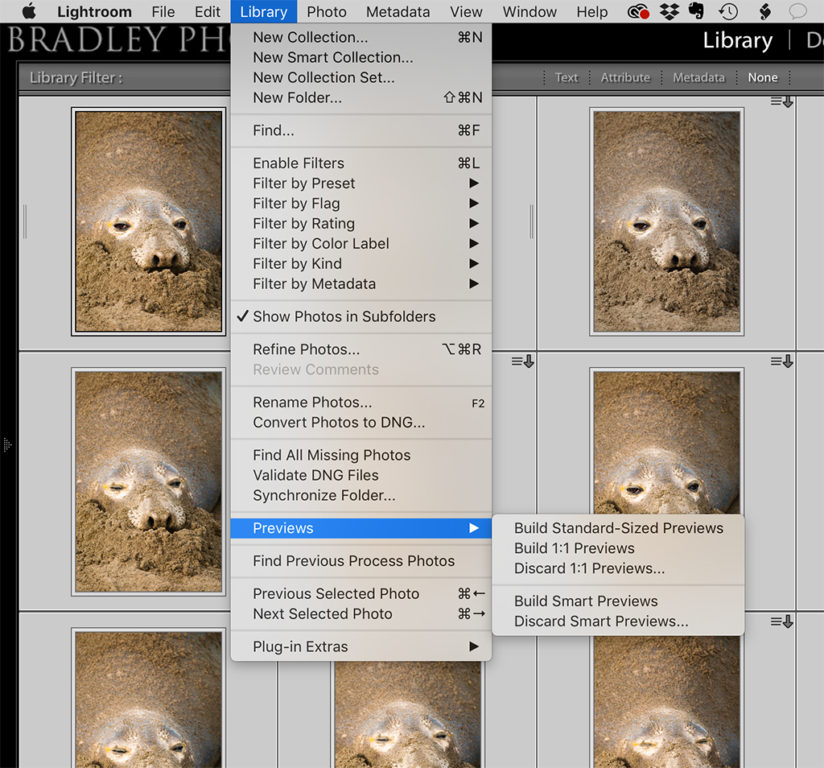

Pro Tip: For the Lightroom Classic user, there is an easy way to know if any of the files you’ve imported have been corrupted. Either during your import or immediately after your import, make sure Lightroom Classic has built a preview for all your files, then simply do a visual inspection and make sure all your thumbnails are intact. Look to the “Build Previews” drop-down menu in the “File Handling” panel during your next import. Simply choose anything other than “Embedded & Sidecar.” Or you can build previews in Lightroom Classic anytime by going to your “Library” and select “Previews” and then choose to build “Standard” or “1:1 Previews” as shown in Figure 4.

Storage Redundancy

Regardless of the hardware you choose, nothing is foolproof. No drive is infallible, no cable or card reader completely dependable, and no human brain immune to mistake. Not to mention, things just happen beyond our control. And so, if there’s anything that I want you take away from this article, it’s that choices in hardware, or tricks in using it, won’t save you.

The best thing to do is to start thinking in terms of storage redundancy. Better yet, think in terms of a bare minimum of triple redundancy, meaning that all your data, in the field, in your home or in your studio, should be backed up, and then backed up again. And we need to develop strategies to make sure that if something happens to our data, that the thing that happened to our data doesn’t get backed up. This means we need safeguards to check the validity of our data as it’s being backed up and be in the practice of not throwing anything away in our backup archives in case data in our primary storage gets erased. Redundancy is the key to keeping digital photos safe.

As I said in the beginning, we will only protect what we love once we are aware of its potential loss. In remaining articles in this series, we’ll explore and detail what protection means. We’ll talk about the tools that are available to us for creating redundancy, such as RAID arrays, specialty drives like Drobo and NAS units. We’ll also talk about archival file formats, validating files, how to structure folder hierarchies on your backup drives, software to synchronize data, and cloud services for online backups, which in turn provide us with remote access to our files. Until then … don’t touch anything!

The post Keeping Your Photos Safe, Part 1: Don’t Touch Anything! appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.