Glasgow-born, London-based David Yarrow created his first major camera-in-hand success with the now-classic image of the legendary Diego Maradona at the 1986 World Cup final in Mexico City for The London Times. Assignments to cover the Olympics and other major sporting events soon followed. These early forays into the world of professional photography gave little clue to where he would end up decades later.

The 21st century has seen Yarrow refocus his energies on creating black-and white-portraits of the great athletes of the natural world, from lions and tigers to orangutans and polar bears. Fusing art and commerce, he has firmly established himself as one of the bestselling fine art photographers in the world with limited-edition prints selling for over $70,000 apiece.

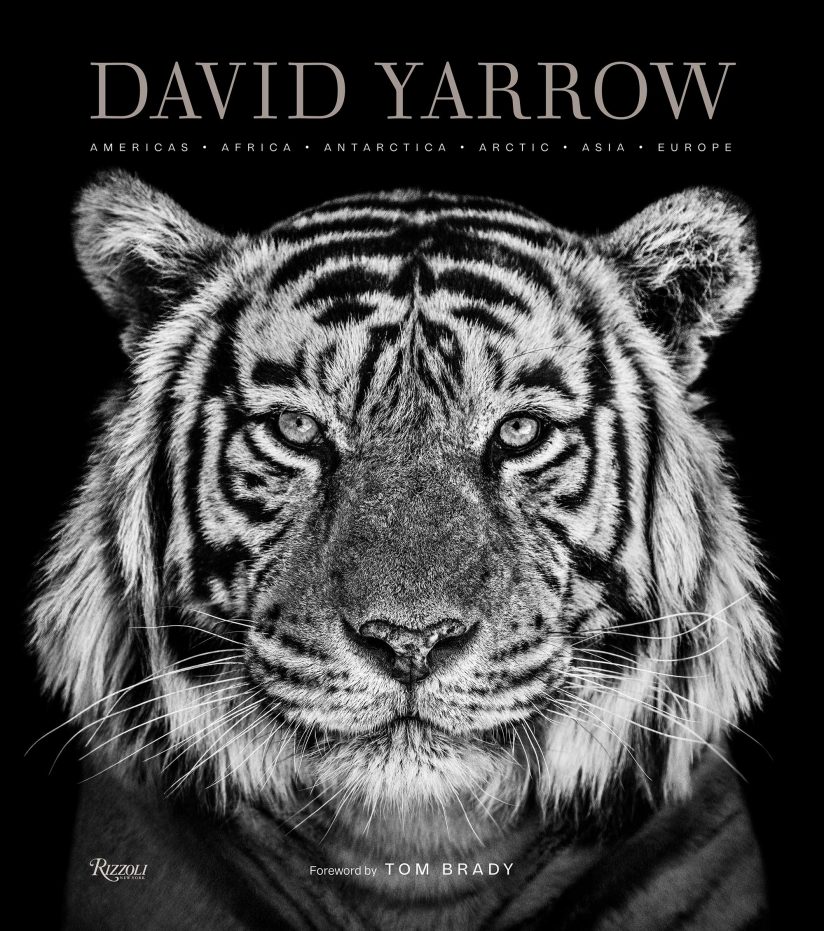

His latest book, David Yarrow Photography: Americas – Africa – Antarctica – Arctic – Asia – Europe (Rizzoli) portrays wildlife on the seven continents with all royalties benefiting WildAid in the United States and Tusk in the United Kingdom.

Outdoor Photographer: What made you decide to work in black-and-white in a genre that is typically photographed in color?

David Yarrow: I guess I’m a scholar of commercial photography in terms of fine art. If you look at the people that have sold fine art photographs of wildlife for the most amount of money before I came along, I would say Peter Beard and Nick Brandt. Much of their work is in black-and-white. I don’t think I’m breaking any new ground there. Black-and-white, because it’s reductive, is perception rather than reality. That lends to the perception that it’s art rather than literal wildlife photography. Black-and-white also lends a degree of interpretation, it’s abstract, it’s not reality. It affords a degree of timelessness. Because I make my income from the art market rather than the editorial market, black-and-white works better for most rooms and office spaces than color does.

“Heaven Can Wait.” Amboseli, Kenya, 2014.

Photojournalist Ted Grant said, “When you photograph people in color, you photograph their clothes. But when you photograph people in black-and-white, you photograph their souls.” This is true for photographing the majority of wildlife as well.

OP: What’s your new short film, “Yarrow: The Virtues of Monochrome,” about?

Yarrow: Our business is an original content business. If I was of the view that I could stay ahead of the game on the basis of talent, I think that would be naïve and incredibly arrogant. There is absolutely no way a photographer can stay on the top purely by having some skill others don’t. There are so many talented photographers around. But what you can do is to continue to invest in the gathering of original content. We have an ability to do that, I won’t say it’s unique, but we can spend half a million dollars on a shoot and pay for it ourselves. It’s incumbent on us to do that to try and get content that other people can’t. I think access and research are integral parts of photography. The film shot on South Georgia [Island] gives insight into how I work.

OP: When most photographers go out to photograph wildlife in places like South Georgia, they tend to pack their longest lenses. You seem to leave yours behind or at least not make them your go-to optics.

Yarrow: We’ve got the odd telephoto lens, but I think it compresses not just in distance but in emotion. We also study the numbers. If you look at photographs in the Sotheby’s and Christie’s auctions—maybe every year 300 go on sale—tell me the number that were photographed with a lens longer than a 300mm? I would say “none.” It’s very difficult to take an image that can be emotional and immersive and memorable with a lens longer than a 300mm. You can if you’re lucky.

“The Breakfast Club.” South Georgia, 2018.

Ansel Adams talked about the lens looking both ways. It looks back into your soul, and that reciprocal relationship diminishes when you magnify.

OP: So how do you get up close and personal with animals in the wild?

Yarrow: I put myself in cages, I use remote controls a lot with lions. With polar bears, I go to places where I can be very close to them on a boat, which they won’t attack. Orangutans, they’re more scared of you, so it’s more about not scaring them.

OP: What’s the most dangerous situation you’ve been in?

Yarrow: I was surrounded by grizzly bears a couple of years ago in Alaska. I got between a mum and her cubs. I stayed still, and they got bored of me. They knew that I hadn’t threatened them at all. If they had been polar bears, that would have been more dangerous.

OP: Your “Mankind” photo is one of your best-selling and most impactful photos in the art world. How did you create it?

Yarrow: It changed my life. I took that photo in South Sudan in 2014. Total sales of that picture are now over 4 million. It reinforced my belief that I could go and do something like that under extreme conditions. We had done a lot of homework. If you look at the pictures from South Sudan, it’s a very dangerous place, and a lot of the photography taken there is very flat. The photographers were all too low. They had no point of raised elevation. Without that elevation, you can’t capture the depth of these Dinka cattle camps. I think a mistake a lot of photographers make is that they don’t do enough research before they go and shoot somewhere. Because I did with my team beforehand, I took a ladder all the way up through a civil war—kind of a strange thing to be doing—because I knew I needed to be 10 feet high. I shot that with a 58mm lens.

“Mankind.” Yirol, South Sudan, 2014.

OP: Do you tend to work with fixed lenses rather than zooms?

Yarrow: The NIKKOR 58mm is my go-to lens. I also work a lot with a 35mm and a 105mm. I never use zooms. You’re not going to see a difference in a picture printed A4 size, but when you make prints the size of a tennis court, you will. One of my pictures is on the side of a building in Oslo. If that had been taken with a zoom, you would know. We do pigment prints up to 60 inches on Hahnemühle [paper] at BowHaus in Los Angeles and up to 80 inches wide in London.

OP: You’ve said in the past that the three most important words for an assignment photographer are “research,” “relentless” and “relevance.”

Yarrow: Of those three Rs, I think the most important is research. Most of our work is done not with a camera-in-hand. I shoot about 90 days a year. A lot of time is used by my team to make sure I’m working with the right people on the ground, at the right time, and that all the logistics are in place.

OP: Hence your teaming up with Natural World Safaris.

Yarrow: Sometimes we’re doing something such as taking a boat and a crew down to South Georgia Island, so we need a fixer like Natural World Safaris for that. We try and take a film crew most places we go because we think creating behind-the-scenes content is so important. It’s not the “what” in 2019, it’s the “how.”

OP: How do you balance all the research and planning with going in with an “empty cup,” so to speak?

Yarrow: I don’t know about the idea that preconception precludes spontaneity—there are always opportunities. We will react to what we see. One thing you can’t completely predict is what the weather is going to do. I prefer bad weather to good weather. Sunshine and blue skies all the time gets boring. We’ll react to weather. We’ll react to animal sightings. The last time I was in Tanzania, the preconception was to work around lions, and I ended up with fairly generic images, but we got a great crocodile shot. I had been waiting a long time for one. I believe that success is 99 percent failure. By getting it wrong, you eventually learn how to get it right.

“10,000 BC.” Tanzania, 2019.

OP: What made the crocodile shot successful?

Yarrow: I quite like photographing animals head-on, getting the animal’s eyes being parallel with my eye line. That just doesn’t work with a crocodile. You have to choose whether to get the teeth or eyes in focus on a big crocodile because the distance is the best part of two and a half feet between them. It is difficult to get both those things in focus unless you are working in such extraordinary light that you have that depth of field. I believe that if the first thing a person sees in the photograph, i.e., the foreground, is not the focal point, there has to be a lot of compensating components in the picture to make it work. If that first thing your eye sees is out of focus, I think you’ve got a problem unless there is something that is so spectacular that brings it all back in together.

I’m obsessed about tension points. With the crocodile, I was having problems because I was attempting to go for both eyes. So the idea became to shoot perpendicular. That conveyed the length. So we looked for a river where I could shoot from the other bank and found a part of the Grumeti where I could do that. Because the whole 12 feet of the crocodile are all the same distance, to me it’s all in focus so there’s a huge amount of textural detail in the image, and because the background is all in the shade, the crocodile stood out. I used a 200mm for the shot.

OP: Let’s talk about your image “Africa” taken in Amboseli in 2018, which both you and the art market consider a career highlight. Did you preconceive having this big-tusked elephant in the extreme foreground with Mt. Kilimanjaro in the background?

Yarrow: No, that’s difficult, albeit that elephant, called Tim, is always within a radius of about 40 kilometers and Kilimanjaro is over 19,000 feet, so it should always be in sight; it’s just a question as to whether you can get it in the background or not. A lot of things coalesced that day. I hired some Maasai guys to locate Tim because he is not collared any longer. When we first located him about 4 p.m., it was quite a difficult thing to just leave him alone for one hour until the light got a little lower and hope he was still in the same place. Fortunately, he was. The person that deserves the credit is the ranger because the ranger knows Tim and knows me. I had to get that low perspective, and you can’t get that from shooting from a Jeep. It’s about triangular trust because I’m on the ground, and I have the biggest elephant in the world charging me. But they do give you three chances. Getting out of the vehicle and having him coming toward me, I would not have done it if I didn’t trust the ranger. That was with a 58mm on a Nikon D850.

“Africa.” Amboseli, Kenya, 2018.

OP: When do you decide to go with a remote rather than putting your eye behind the lens?

Yarrow: The genesis of the remote stuff was a lioness photo I did in 2011. We scented the cameras with Old Spice aftershave that the Maasai wear, a holdover from British colonial rule. I don’t know if it works, and I don’t do it anymore. In the old days, we used to put cameras in metal boxes. I don’t do that any longer, either, because it is a pain in the neck to set up and too heavy to lug around. What we discovered was that if a lion comes up to the camera and grabs it, they won’t destroy it; they might take it and damage it, but after two minutes, they’ll get bored and drop it so we can retrieve it and get the card back. Hyenas, however, will destroy a camera.

A lot of film crews set up their remote systems so they can see what’s happening through the computer. I don’t have time to do that. We are setting these things up with about three seconds to get out and then back in the jeep.

OP: You’re not setting up cameras with motion detectors?

Yarrow: No. I have huge admiration for people who set up cameras in the Himalayas and get a snow leopard, but I would argue that this is the difference between reportage and art. You have no control over the composition and the light. If it happens, it happens.

OP: What’s the backstory for your “78 Degrees North” image?

Yarrow: One of the great American photographers, Diane Arbus, said, “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” I think there’s a lot of validity in that. We live in an age where we are quite keen to story off ourselves rather than being told this is the story. Anything that offers a degree of interpretation, where the interpretation can be left to the viewer’s mind, tends to work as an opening premise. That picture can mean all sorts of things. It can be a message about solitude. It could be a story about the diversity of our planet. It could be used for an advert.

“78 Degrees North.” Svalbard, Norway, 2017.

Because it is reductive, because there’s so little in it, it actually helps the image. As soon as I took it, I knew it was a big shot. I just never thought people would be paying 100 grand for it. It sold out so quickly in part because it’s so unusual.

I’ve got conviction on a lot of things, but I don’t think I have an ego, and I do believe that luck plays a big role and that was a lucky shot. The fact that he’s going up an incline and walking away from me makes the picture.

OP: Perhaps a better word is fortunate rather than luck. You put yourself in a place for things to come together, and you had the skill and the vision to translate it into an image at the decisive moment.

Yarrow: I work a lot with the golfer Gary Player. There’s a quote attributed to him, “The more I practice, the luckier I get.”

See more of David Yarrow’s work at davidyarrow.photography.

The post Into The Wild appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.