This past January, a newsflash spread like wildfire through the landscape photography community. According to a report circulating online, Zion National Park had banned use of tripods by photo workshop groups. If the claim were true, landscape photography workshops at Zion National Park would be essentially pointless, and many of my professional peers expressed shock, disbelief, frustration or outrage.

By the end of the month, following a torrent of inquiries and criticism, the park issued a statement by Philip Arrington, Zion’s concession management specialist, clarifying that while use of tripods by commercial workshop groups was not permitted on trails, it was permitted in certain designated locations, such as at roadside pullouts. Also, the fine print of the regulations governing workshops stated that “groups may travel on foot up to 100 feet off of designated trails, using existing disturbances or staying on hardened surfaces.”

One could reasonably deduce from these stated policies that the tripod restrictions were focused, in spirit, on addressing the obstruction of visitor foot traffic and potential public safety hazard that could result from the use of tripods on the park’s most popular pedestrian pathways. Perhaps if the workshop group was off trail and in an area that wasn’t sensitive to damage due to trampling (such as on slickrock, in a sandy wash, or on a gravel river bank, as opposed to on vegetation or fragile cryptobiotic soil crusts), then they were good to go.

Unfortunately, it isn’t that simple. After reviewing the regulations and speaking at length with the very helpful Ranger Arrington, I’d like to offer some clarity regarding the current rules related to use of tripods at Zion National Park. To cut to the chase, I can confirm that tripods are essentially banned from use by commercial workshop groups in areas accessed by trailheads in Zion Canyon.

Details Of The Tripod Ban

- The good news for solo photographers: Most visitors to Zion National Park may continue to use tripods as they always have. Unless you visit the park as part of a commercially guided group, you are free to use a tripod where you like, with obvious exceptions like in the middle of roadways, vegetation restoration areas, and any other areas that may be closed to entry by the general public.

- The good news for workshop groups: Along the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway (Route 9) through the Zion high country, it is permissible for commercial workshop groups to park at designated pullouts and use tripods within 100 feet of the roadway in areas that can be accessed via hard surfaces or naturally disturbed areas, such as the slickrock and sandy washes.

- The bad news for workshop groups: Visitors participating in or leading commercial photography workshops may not use tripods on trails in the park, and that doesn’t mean quite what you think it does…

- The definition of “trail:” As used by Zion National Park, the word “trail” refers not only to the pathway itself and is more properly understood as the use area that is accessed from a particular trailhead. In other words, if a workshop participant sets up a tripod on a gravel bank of the Virgin River accessed via the paved Riverside Walk, they are still considered to be “on the trail” even though they are not set up on the path itself. The same is true for other trail-accessed areas in Zion Canyon, such as Emerald Pools Amphitheater, the Virgin River Narrows (in which case the river itself is the trail), Angels Landing Trail, Weeping Rock and so on. This means that tripods are effectively banned for use by commercial workshops in any area accessed by a trail in Zion Canyon.

- Areas available to workshop groups: The park provides a list of trailheads and trails (remember, these are broadly interpreted as the area accessed by the trail, rather than the actual pathway itself) that are permissible for use by commercial photo workshop groups, though they still can’t use tripods in these locations. The regulations state that guiding in any other area of the park is a violation.

- Wilderness: Commercial guiding is not permitted in any of Zion’s 124,000 acres of designated wilderness, which makes up 84 percent of the park. The wilderness is otherwise open, but visitors should check with the park website or office regarding current conditions, possible trailhead closures, safety considerations and permits, which are required for all overnight trips, including climbing bivouacs, all through-hikes of The Narrows and its tributaries, all canyons requiring the use of descending gear or ropes, and all trips into Left Fork (The Subway).

Frankly, having operated several Visionary Wild photo workshops at Zion in recent years, the new restrictions on photo workshops don’t come as a surprise to me. The park staff at Zion have been coping with a massive increase in visitation in the wake of a very successful international campaign launched by the state of Utah to promote its national parks. Zion is the most accessible to tourists flowing in from Las Vegas, so it has borne the brunt of increased visitor traffic. Before 2014, Zion had never exceeded 3 million visitors in a year. In 2017, it set a new record, with 4.5 million visitors, making it the third-most-visited park in the whole national system. In comparison to Great Smoky Mountains and Grand Canyon—the first- and second-most visited parks, respectively—which have comparatively more area over which to distribute visitors, the topography of Zion National Park compresses visitors into very tight spaces, creating serious issues of crowding, traffic flow (both pedestrian and vehicular), focused impacts to vegetation and soils, and even a problem with human waste in the Virgin River Narrows.

Commercial users of public lands are always subject to stricter regulations than the average visitor, and I have no doubt that the park managers have targeted photo workshop groups out of need to address realities confronting them, and not because they have something against photography enthusiasts. Even before the “tripod ban,” however, Visionary Wild had shifted our canyon-country workshops to less-crowded locations elsewhere on the Colorado Plateau. Though we love Zion, we’ve found that the crowds there make it impossible for us to meet our goal of delivering an excellent-quality overall experience for our clients, so we haven’t operated there since 2015.

Planning For The Future

Change may be afoot, however. The National Park Service has initiated a new Visitor Use Management planning process for Zion that will result in a new management plan and commercial services strategy. An end to the tripod ban is possible, and the public is encouraged to participate in this process. Information can be found online at parkplanning.nps.gov.

The situation in Zion is a reminder that managing our federal lands and their resources can be a tough and thankless job, whether at the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the U.S. Forest Service. The National Parks tend to be the most highly regulated and restrictive, as their mandate is to conserve park resources and values to ensure that they can be enjoyed by future generations. When there is a conflict between conservation and the human use of a national park, conservation generally wins, as it should, in my opinion.

The BLM and Forest Service have much broader multi-use mandates that range from the preservation of designated wilderness to recreation to management (and in some cases facilitation) of commercial activities such as logging, mining, oil and gas drilling, renewable energy production and livestock grazing. All of these agencies encourage visitation by the public, as well as recreational and commercial uses that are regarded as appropriate in relation to their respective missions and management plans.

Most of the people who choose a career with our land management agencies take public service very seriously, they care deeply about the places for which they are responsible, and they do their best to maintain balance and fairness of regulation in the interest of the various constituencies that make use of the land. And they do so with very limited resources. Keep in mind that the annual budget for the entire National Parks System is only about $2.5 billion—roughly equivalent to the cost of a single B-2 stealth bomber.

Over more than two decades working with public lands managers, I’ve found that they welcome passionate photographers with open arms, and most view serious nature photographers as allies in the stewardship of our national treasures. “When it comes to our park’s experience with photographers,” says Big Bend National Park Ranger Jennette Jurado, “we do find that many of our visitors, commercial and not, that make the effort to come all the way down here usually are the type that understand our need to protect and preserve this landscape, and therefore are respectful of the regulations that are in place to that end.” Ranger Arrington at Zion considers photo workshop operators and other commercial use permittees in general to be assets to the parks, augmenting the NPS mission by teaching natural history interpretation, conservation practices and safety.

Rangers also have a lot to offer us and want to be helpful. Robert Jolley, a division chief with the Bureau of Land Management, which administers 247 million acres of public land, nearly an eighth of the land mass of the United States, urges photographers to visit the local field office when they visit BLM lands, including such gems as Grand Staircase-Escalante, Bears Ears or Vermilion Cliffs National Monument. The staff at local offices and ranger stations of all the agencies are excellent sources of information about photo opportunities, their personal favorite places, seasonal conditions such as the wildflower or fall color forecast, rules and regulations, and issues of access and safety. If you are headed off into backcountry areas featuring natural hazards such as slot canyons prone to flash flood, or an area at risk of wildfire during the dry season, it’s good to let the rangers know (even if a permit isn’t required, which it may be in some locations) so they can both advise you and be aware of your plans. Also, on lands with a multi-use mission, they can inform you of unexpected potential hazards, such as open mine shafts, the presence of hunters during deer season, the possibility of encountering unexploded military ordnance or the fact that cute wild burros can be rather ornery.

The reality is that the relationship between outdoor photographers and public lands managers can be a mutually beneficial partnership, but that means we have to uphold our end of the bargain as well, whether we are amateur photographers making pictures for pure enjoyment or pros making a living. We can begin by recognizing that our activities can have impacts that potentially degrade the places that we love, detract from other visitors’ enjoyment or perhaps even create serious safety issues.

Our choices and actions can ultimately affect policy, which can make access and rules on public lands more restrictive for everyone. Over the years, there have been incidents in which professional photographers (and I won’t name names) have been caught doing unconscionable things on protected lands, such as illuminating Delicate Arch with Duraflame logs and scarring the rock in the process, staining Coyote Buttes’ lovely striated sandstone with blue-smoke pyrotechnics during a fashion shoot, sawing off blooming rhododendron branches in order to position them just-so in a Northern California redwood forest, and more. Fortunately, this selfish minority is outweighed by the grand majority of serious amateur and professional nature photographers who are responsible and respectful of rules. This is particularly true of most commercial photo workshop leaders, as in order to obtain and maintain their permits, they are required to follow Leave No Trace guidelines, minimize impacts and explain responsible practices to their clients.

New Technologies, New Challenges

Those unfamiliar with rules, regulations, conservation ethics and the priorities of lands managers tend to cause more problems in their desire to “get the shot.” According to Neal Herbert, a photographer and digital communications specialist at Yellowstone National Park, “The primary impact we see is people getting too close to wildlife, or pursuing them, to get a picture. In most cases, these are individuals with smartphones trying to get a shot that really requires a telephoto lens.”

This problem extends to the widespread use of drones for photography and video, which has opened a Pandora’s Box of challenges to the balance between photographers’ interests and land management priorities. National Parks have responded by banning their use outright, as have the Forest Service and BLM in designated wilderness, though otherwise their use is commonly allowed so long as drones are kept a healthy distance from wildlife. In National Marine Sanctuaries, for instance, drones may not be flown within 1,000 feet of a whale. Generally speaking, if animals react to a drone’s presence, it is too close.

Drones can also disrupt fire and rescue aviation, according to Jody Weil, the BLM’s Arizona director of resources and planning, who points out that drones (as well as private aircraft, for that matter) may not be flown in any area where firefighting activities are taking place. A single drone in the air means that aircraft engaged in fire and rescue operations must be immediately grounded for safety reasons, which can cost lives, not to mention valuable property and the health of the resource itself.

It would be impossible to comprehensively cover the range of activities relevant to photographers that might be prohibited on some public lands and permitted in others, but prohibitions may include the following:

- Guiding commercial workshop groups without a valid permit, proper insurance, first aid/CPR certification, payment of permit fees, etc.

- Guiding commercial workshop groups to sensitive cultural sites like petroglyphs and pictographs.

- Exceeding the local workshop group size limit.

- Spotlighting animals at night.

- Light painting features in the landscape, or doing so without a specially arranged permit.

- Setting up tripod legs on the ground in areas where boardwalks have been built to protect fragile surfaces, such as the geothermal areas at Yellowstone.

- Setting up tripods in roadways.

- Driving off road.

- Walking on playas when they are wet (leaving enduring tracks in the process), such as the Racetrack in Death Valley National Park.

- Climbing on, toppling or otherwise damaging fragile rock formations.

- Lighting fires or creating other fire hazards, such as using pyrotechnics, or engaging in the recent trendy practice of slinging showers of sparks from burning steel wool around during long exposures at night.

- Baiting, harassing or otherwise disrupting wildlife.

- Picking, cutting or destroying live vegetation.

- Picking, cutting or destroying dead vegetation.

- And on, and on…

The point is that it’s a good idea for us to consider the advice of Jolley at the BLM: to make use of the public resources available to us, ask questions and do our homework on rules and best practices so that outdoor photographers can act in effective partnership with our public lands managers as leaders, role models and good stewards of these incredible landscapes and ecosystems that belong to all of us.

Personally, it excites me to no end that by birthright alone I am a part owner of places like Yosemite, Yellowstone, Denali, Grand Staircase-Escalante, the Grand Canyon and, of course, Zion. I know that I am not alone.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

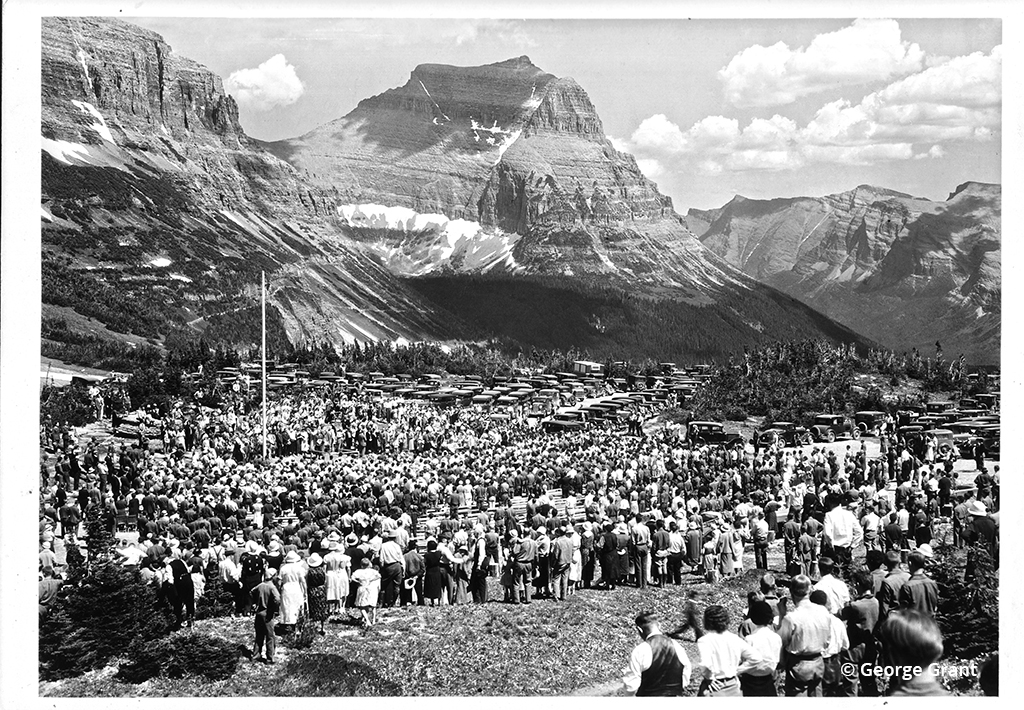

Parks For The People

George Grant toiled in obscurity for nearly three decades as the first official photographer of the National Park Service. Ren and Helen Davis want to make sure his story isn’t lost to history. Read now.

The post Understanding The Tripod Ban appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.