The sun rises above Nyungwe as the mist lifts from the forest. This is a single shot from a long time-lapse we created that reveals the flow of the clouds.

The close of the 20th century was a dark time for the people of Rwanda. The 1994 genocide during a four-year civil war took the lives of an estimated 500,000 to 1 million people. This had not only a tragic human impact but also an environmental one as well. Refugees returned in chaos, many having lost their lands, and took up subsistence farming, clearing vast expanses of ancient forest in the process. An archived web page at NASA.gov estimates that in the years between 1986 and 2001, only “1,500 acres of the [Gishwati] forest’s original 250,000” remained.

Things are looking brighter for Rwanda in the 21st century. In 2004, Nyungwe Forest National Park was established. About 30 miles to the south of Gishwati Forest, it encompasses the largest remaining forest in the African nation. In 2007, the Gishwati Area Conservation Program formed to protect the remaining forest there. These efforts are a tremendous win for the wildlife and biodiversity of the region.

Workers pluck the young leaves in the tea fields at the edge of the forest. These fields act as the demarcation of the Nyungwe boundary, clearly showing people the protected area.

This is where “A Walk Through the Land of a Thousand Hills” begins. Filmmaker and cinematographer Chema Domenech spent two weeks traversing Nyungwe park with Claver Ntoyinkima, a son of this forest and one of its wardens today. In just over 11 minutes, the film immerses you in a magical landscape through the eyes of Domenech’s remarkable guide. We talked with Domenech about the experience.

Outdoor Photographer: What about this place was the inspiration behind the film?

Chema Domenech: As Claver Ntoyinkima says in the film, Nyungwe is a magnificent forest. The wildlife of this forest is so incredibly diverse, and so is the flora. I think you could make an entire natural history series about the forest and barely scratch the surface. But what struck me the most while making this film was the relationship that people have with forest. In contrast to U.S. National Parks, Nyungwe is not isolated from the daily rhythms of people’s lives.

A colobus monkey holds an infant high on the canopy. They are born completely white and grow into their long flowing black and white fur.

Our approach to the film was deeply influenced by the work of Dr. Amy Vedder and Dr. Bill Weber. I got to know Amy and Bill while my partner was working on her master’s at the Yale School of Forestry. Their conservation work is strongly based on the idea of including rather than excluding people from the landscapes they are working to protect. This is most evident in their work with mountain gorillas in Rwanda. We wanted to follow in their footsteps and make a film that highlighted the positive interactions between the human and non-human worlds. As we got to know Claver, his life and his relationship with the natural world really inspired the film as it is today.

OP: How did the project begin?

CD: In the fall of 2018, I approached Amy and Bill about a few film topics that I was researching in Rwanda. When making a documentary, you always have to be open to other possibilities. Amy and Bill began telling me about their good friend Claver Ntoyinkima. I knew instantly that this was a story that needed to be told.

A chimpanzee rests against a tree while munching on figs on the forest ground.

Amy and Bill put me in contact with Claver, and we had several conversations over the phone. His brimming smile came across the airwaves. He is the kind of person you instantly want to be friends with. We discussed our mutual love for birds; I would later learn that Claver is one of the best birders in the world. I have never been with anyone that can spot or identify a bird quite like Claver. I told him about the idea for the film, and from there, we began working on a plan.

OP: What were the logistical challenges? Did you need permits from the Rwandan government?

CD: We did need permits from the government. Amy and Bill were kind enough to introduce me to Michel Masozera, a senior staffer for World Wildlife Fund’s Africa program living in Rwanda. He then introduced us to his colleagues Tony Mudakikwa and Richard Muvunyi at the Rwanda Development Board. RDB is in charge of the Rwandan national parks. They were incredibly generous with their time and resources and served as important advisors throughout the process of making this film. We really could not have done it without their help.

A mating pair of grey crowned cranes feed on the agricultural fields of Banda at the edge of Nyungwe. Their numbers are a fraction of what they used to be, but efforts to rescue cranes from captivity and reintroduce them to certain areas of Rwanda are succeeding.

Traveling to Rwanda from the U.S. takes quite a bit of time, especially if you live in Bozeman, Montana—there are no flights to Kigali from out here. It took us about 36 hours from when we left Bozeman to when we arrived in Kigali, and I would highly recommend spending at least one night in Kigali if you are planning on making this trip.

Getting all our gear from Montana to Rwanda was a challenge. We had over eight checked bags and four carry-ons in total. Normally, this would be prohibitively expensive, but airlines have a media rate, and we were able to take advantage of it and it only cost us about $250 to fly our gear out there.

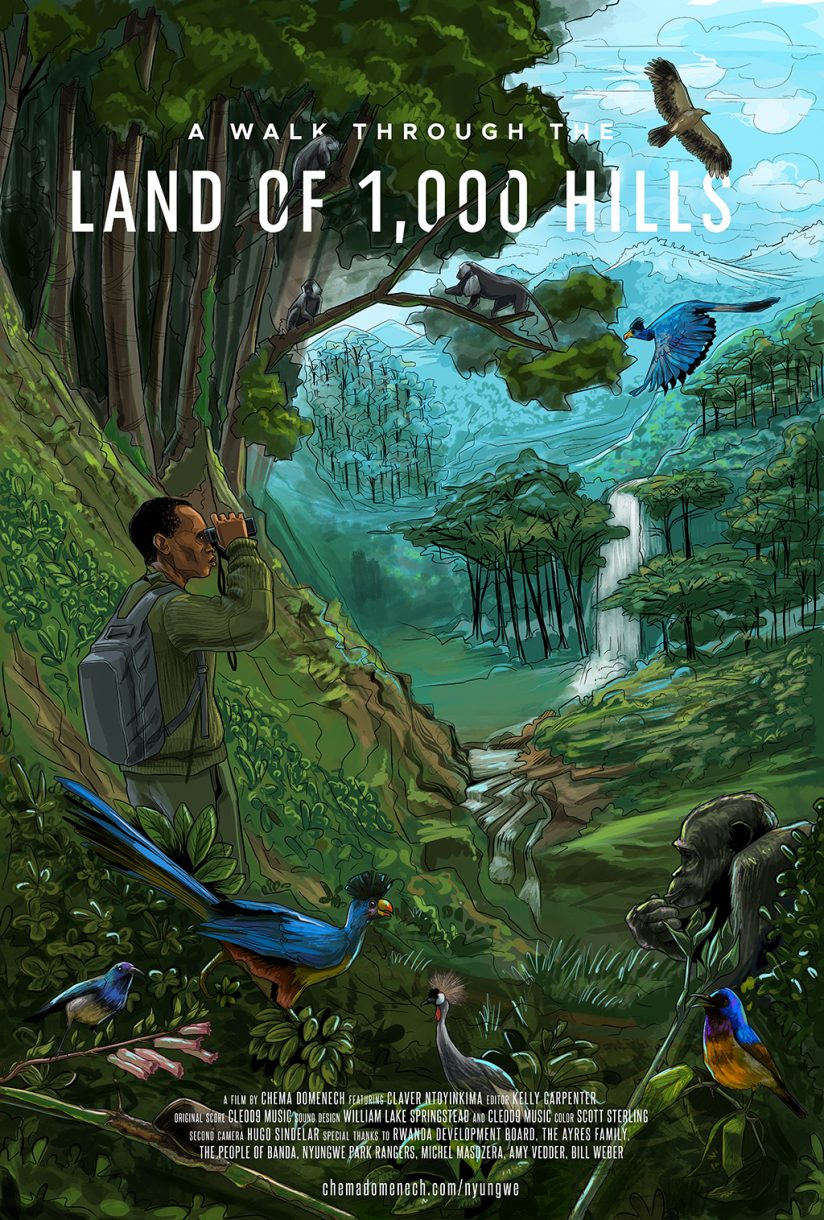

We stayed at the Gisakura Guest House, which is about a mile and a half from the Nyungwe entrance. Most people only stay for a few nights, but we were there for almost two weeks, so we became good friends with the staff. At night we would sit with the manager, Joseph, and chat about the film and learn about each other’s lives. This was also where one night we met the artist that designed the poster for this film. It is just incredible how generous and friendly people are around Nyungwe.

OP: Did you have a clear idea of the story you wanted to tell, or did it evolve during filming?

CD: I began by reading Amy and Bill’s book, In the Kingdom of Gorillas: The Quest to Save Rwanda’s Mountain Gorillas, which is more about their work with the Mountain Gorilla Project, but it covers their work all over Rwanda, including a chapter about Nyungwe.

I tried to have as many conversations as I could with Claver before we got there. Claver spends a lot of time in the forest, so this was a challenge. I had planned interview questions and had a rough idea of what I thought the final film would look like, but I remained open to the possibility it would gain a life of its own while we were there.

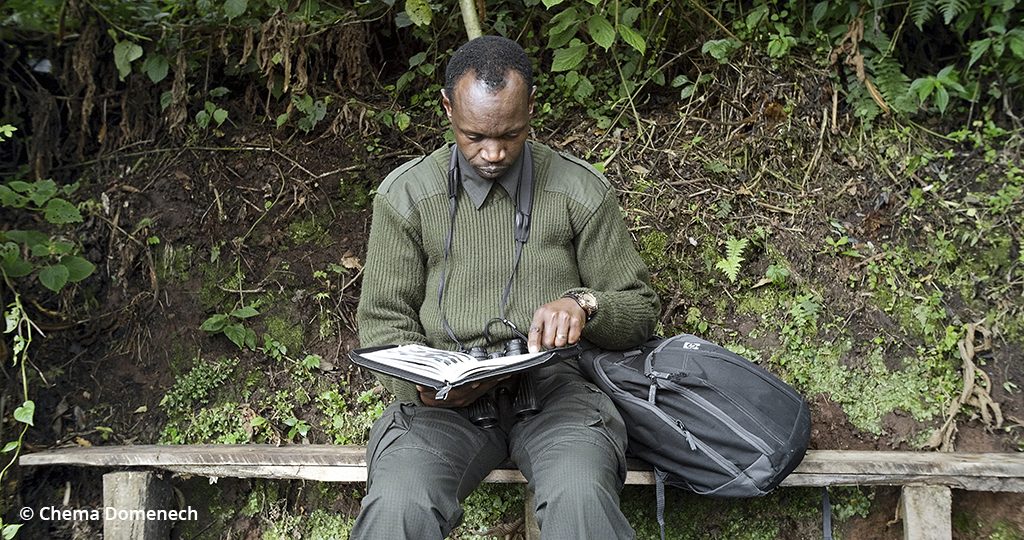

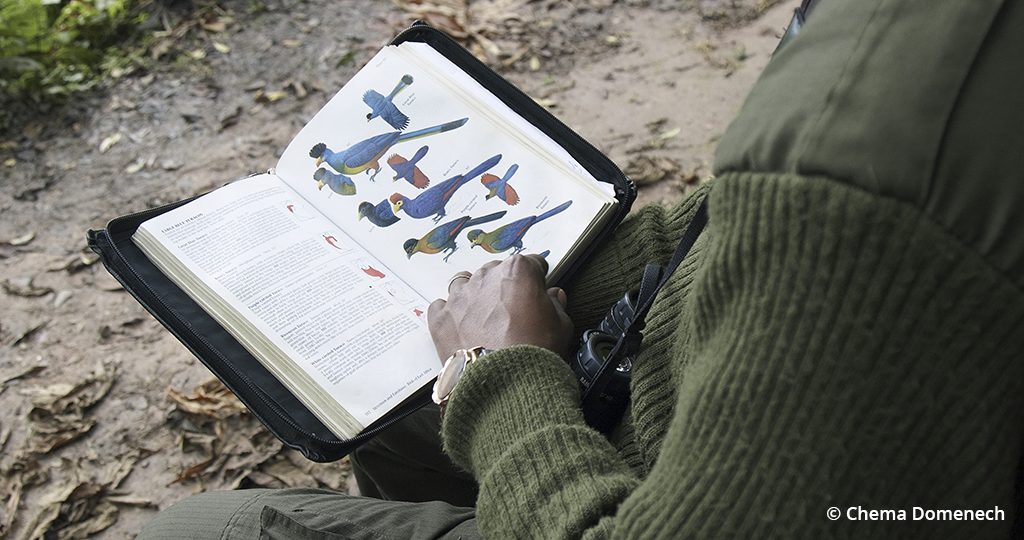

Claver spends 300 days of the year walking the forests. He knows the forest intimately, but he uses his field guide from time to time to show others what they are looking at while also giving them a chance to rest.

Claver flips through his field guide to show us the very restricted range of the Rwenzori turaco.

The Rwenzori turaco is endemic to the Albertine Rift, where Nyungwe is located. It is one of the most colorful birds in the forest and one whose call echoes from the treetops throughout the day.

Claver is a natural-born storyteller and once we started recording it really became his show, and we adapted around him.

OP: How long did the filming process take?

CD: We were in Rwanda for two weeks and filmed for 12 hours almost every day, taking a few breaks here and there.

OP: What equipment did you use?

CD: We shot almost everything with a Panasonic GH5s, recording on an Atomos Ninja and using the Sigma 150-600mm lens and occasionally the Sigma 300-800mm, which is a beast. We had a heavy and sturdy Cartoni head and tripod. We also used a motion-controlled slider and a handheld gimbal for some of the shots. Our second camera was a Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, and we also used a Nikon D850 for some of the time-lapse work.

OP: Did you have a team on the ground with you or was this a solo project?

CD: This project was a huge team effort from pre-production to finished product. A friend of mine, Hugo Sindelar, helped me with the filming process in Nyungwe. He ran the sound for the interviews and the second camera. In addition, we had help from Claver and his friends carrying our equipment through the Nyungwe Forest and relaying information about the wildlife.

Domenech behind the camera surrounded by local guides and curious helpers.

OP: What were your biggest challenges while filming?

CD: Our treks to find the chimpanzees were the most challenging days. They took us through the thick underbrush and up some very steep and muddy slopes. We were also trying to move quickly but quietly, so Claver and I would split the load, one of us carrying the tripod and the other camera, which was always set up and ready to go, so we could film as soon as we stopped.

When we visited Banda, where Claver is from, we hiked 13 miles and carried all of our equipment with help from three of Claver’s friends. Most people will tell you it is not an easy hike, let alone carrying the amount of stuff we were carrying, but these guys made it look effortless.

OP: Will the film be used to further conservation efforts in Nyungwe?

CD: My hope is that the film helps Claver get his wish of Nyungwe achieving World Heritage [status with UNESCO] but that requires a greater global awareness of the importance of the park. A significant portion of tourism proceeds get distributed back into the communities surrounding Rwanda’s national parks. As Claver explained to me, this garners greater support from locals for the conservation of these wild places.

I also hope that the film inspires others to visit this hidden gem of Rwanda and therefore aids in maintaining local support for the park.

OP: Has Claver seen the film? What was his reaction?

CD: Yes! Amy traveled to Rwanda this past summer and took a copy of the film with her. She was accompanied by a group of students, and they showed the film to Claver.

The film cover artwork was designed by a local who Domenech met at the Gisakura Guest House where he stayed during filming.

When she returned to Kigali, I got an email from her saying that Claver “was tremendously pleased—smiled a beautiful, big ‘Claver smile’ the entire time.” Knowing that he had that big “Claver smile” made me so happy and proud of the entire team.

OP: What will you remember most from the adventure?

CD: This is a hard question because the whole experience with Claver is so unique. But there is a moment that I think about most often. We were filming the great blue turaco, a striking multi-colored bird, on the trail that goes down to Banda. An older woman was making her way up the trail. As she got closer to us, Claver said hello and exchanged a few words with her, then she came closer to me.

At this point, we had been in Rwanda for about a week, and I had learned a few words. I said hello in Kinyarwanda and she politely said hello back, and when I continued to ask how she was doing, she grinned and gave me a traditional embrace—I couldn’t help but grin, too! A few seconds later, she realized it was all I knew when I had to ask Claver what she was saying. The three of us laughed as she continued on her way as she said “mukomere” (walk strong), a traditional farewell.

Editor’s Note: In January 2020, following this interview, “A Walk Through The Land of 1,000 Hills” received the 2020 Student Filmmaker Award from the Wild & Scenic Film Festival.

See more of Chema Domenech’s work at chemadomenech.com. Learn more about the film at nyungwefilm.com.

The post Filming In The Land Of 1,000 Hills appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.